That’s the import of remarks by Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Kevin Washburn, testifying before a Senate committee. Not only have revenues plateaued in the $26 billion-$28 billion range, they’ve essentially been the same since 2007. Meanwhile, private-sector gambling is outstripping tribal revenue growth, hitting $38 million last year.

That’s the import of remarks by Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Kevin Washburn, testifying before a Senate committee. Not only have revenues plateaued in the $26 billion-$28 billion range, they’ve essentially been the same since 2007. Meanwhile, private-sector gambling is outstripping tribal revenue growth, hitting $38 million last year.

“No great economic resource lasts forever,” summarized Washburn, head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and a member of the Chickasaw Tribe of Oklahoma — which has more than a few gaming irons in the fire. He admitted to a certain bias: “Commercial gaming goes to enrich shareholders. Indian gaming goes to help poor people, usually. I would much rather see Indian gaming existing than commercial gaming expanding.”

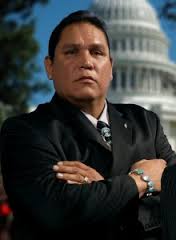

National Indian Gaming Association Chairman Ernie Stevens took a more upbeat view, saying, “Welcome to our world. Indian country has always had to deal with those challenges.” He cited some overwhelming statistics, such as 665,000 people employed across 445 tribal-gaming ventures. Noting the triple level of oversight (federal, state, tribal) with which some tribes must cope, Sen. Heidi Heitkamp (D-N.D.) suggested a more laissez-faire approach. “We need to rethink the regulatory structure,” she said. “I think at some point we anticipated [a] problem that haven’t shown up.”

National Indian Gaming Association Chairman Ernie Stevens took a more upbeat view, saying, “Welcome to our world. Indian country has always had to deal with those challenges.” He cited some overwhelming statistics, such as 665,000 people employed across 445 tribal-gaming ventures. Noting the triple level of oversight (federal, state, tribal) with which some tribes must cope, Sen. Heidi Heitkamp (D-N.D.) suggested a more laissez-faire approach. “We need to rethink the regulatory structure,” she said. “I think at some point we anticipated [a] problem that haven’t shown up.”

Texans get pretty sensitive about casino-style gambling whenever it’s proposed. A push for electronic bingo drew so much umbrage that it’s on hold, pending further review. Now “instant racing” (replays of historical races, minus the identifying data) is in the spotlight. You can guess the objection: If it plays like a slot, looks like a slot and pays out like a slot, it’s a slot. However, proponents say the machines are in compliance with parimutuel gambling.

State Rep. Dan Flynn (R, below) thought the Texas Racing Commission was trying to get instant-racing machines into the Lone Star State on the sly and he’s asked the attorney general’s office to look into the matter. “When agencies jump out and do things, often, they think no one is really watching,” rationalized Flynn.

Proponents of the machines are treating the slot question as moot: “Supporters say this form of instant racing is needed to help struggling Texas racetracks compete with out-of-state tracks that boast casinos, bigger crowds and bigger purses.” Kentucky, which doesn’t allow the slots, permits instant racing and has seen the devices gross $30 million– at just two tracks in a single month. Do Texas legislators have the salt to pass up that kind of payday for the state?

Proponents of the machines are treating the slot question as moot: “Supporters say this form of instant racing is needed to help struggling Texas racetracks compete with out-of-state tracks that boast casinos, bigger crowds and bigger purses.” Kentucky, which doesn’t allow the slots, permits instant racing and has seen the devices gross $30 million– at just two tracks in a single month. Do Texas legislators have the salt to pass up that kind of payday for the state?

The debate has broken down on predictable lines. “The proposed rules would dramatically and illegally expand gambling in the state of Texas by authorizing slot machine gaming at state-licensed horse and greyhound tracks,” writes the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas. Meanwhile, horse breeders Nancy and Robert Morgan counter that thousands of jobs will be saved by allowing racinos: “The Texas horse industry is relying on your belief that ours is an industry worth preserving.”

It’s unfortunate to see Texas’ horseracing industry withering on the vine thanks to the Victorian moral scruples that hold sway in the statehouse. But let’s not kid ourselves: It is an educated form of slot machine. If lawmakers can deal with that reality, we might get somewhere.