Donald Trump‘s current ubiquity is causing the spotlight to fall upon his many setbacks in the gaming industry. “If you look at anything that guy has done in this industry, he has a  lead thumb — it’s the opposite of a golden touch,” says blogger par excellence Victor Rocha. One instance of this is the former Spotlight 29, a California bingo parlor run by a 12-member tribe, the Twenty-Nine Palms Band of Mission Indians. Trump talked his way into a management contract, built Spotlight 29 into a Class III casino and rebranded it Trump 29.

lead thumb — it’s the opposite of a golden touch,” says blogger par excellence Victor Rocha. One instance of this is the former Spotlight 29, a California bingo parlor run by a 12-member tribe, the Twenty-Nine Palms Band of Mission Indians. Trump talked his way into a management contract, built Spotlight 29 into a Class III casino and rebranded it Trump 29.

The deal was announced a day after California voters passed Proposition 1A in 2000, legitimizing tribal casinos in the Golden State. The Twenty-Nine Palms Band would build a $60 million casino, partly financed by Trump. In return for the Trump brand, the mogul would get a 30% cut of the proceeds. At the ribbon cutting, Trump delivered a typically empty threat: “I think Las Vegas is in serious trouble because of what is happening in California.” (To be fair, a few Las Vegas casino execs fearfully shared the same sentiment.)

Three years later, he was out, two years early, his contract terminated in return for $6 million, negotiated down from a contracted $11 million. (An Indiana riverboat contract was similarly short-lived.) At least — unlike his dealings in Atlantic City — he had cut a good bargain for himself this time, his company collecting $13.5 million in management fees in three years, if well short of the $21 million projected.

The tribe ignored warnings from the California Nations Indian Gaming Association that Trump was looking to exploit them. But when the Trump brand delivered lower-than-expected financial results, The Donald was out and the casino  reverted to being Spotlight 29. Current tribal chairman Darrell Mike concedes that at least the tribe got a good casino facility out of “a marriage that didn’t work out” (a subject on which Trump is something of an expert). More to the point, once the tribe had learned the ropes of running a casino, they wanted Trump gone. Period. “They didn’t really appreciate that Trump had put up money, had put in slots, and had helped get the money to rejuvenate the place. That was done, the casino was up and making money, and they didn’t think they needed him anymore,” says a Trump defender.

reverted to being Spotlight 29. Current tribal chairman Darrell Mike concedes that at least the tribe got a good casino facility out of “a marriage that didn’t work out” (a subject on which Trump is something of an expert). More to the point, once the tribe had learned the ropes of running a casino, they wanted Trump gone. Period. “They didn’t really appreciate that Trump had put up money, had put in slots, and had helped get the money to rejuvenate the place. That was done, the casino was up and making money, and they didn’t think they needed him anymore,” says a Trump defender.

Trump’s 2004 bankruptcy provided Twenty-Nine Palms with the opportunity to buy Trump out of Trump 29. Casino revenues there were ramping up sufficiently that, had he

been able to sustain the contract, he’d have eventually collected $20 million, not $6 million. In typical Trump fashion, he even took a bath on the buyout. Other than a nightclub and a Trump bobble-head in Darrell Mike’s office, you won’t find many souvenirs of the Trump era. The tribe, meanwhile, expanded and prospered, opening a second casino, near Joshua Tree National Park. “They figured out pretty quickly that this guy was not what he said he was,” concludes Rocha, “and they could do a better job. And they have.”

been able to sustain the contract, he’d have eventually collected $20 million, not $6 million. In typical Trump fashion, he even took a bath on the buyout. Other than a nightclub and a Trump bobble-head in Darrell Mike’s office, you won’t find many souvenirs of the Trump era. The tribe, meanwhile, expanded and prospered, opening a second casino, near Joshua Tree National Park. “They figured out pretty quickly that this guy was not what he said he was,” concludes Rocha, “and they could do a better job. And they have.”

Not that it wasn’t in Trump’s nature to smear Native Americans when it served his purposes. His habitual, ill-concealed racism surfaced at a hearing of the House Native American Affairs subcommittee when he said of the Mashantucket Pequots, owners of Foxwoods Resort Casino, “they don’t look like Indians to me.” The latter’s sin? They had the temerity to compete against Trump in the casino business. Not content with impugning the tribe’s ancestry, Trump insinuated that tribal gaming was rife with Mafia ties — an accusation more accurately aimed at Trump’s own construction ventures.

He would later use similar tactics against the St. Regis Mohawks. “He has always been hostile to tribal gaming because he considers any competition a personal affront,” says Trump biographer Michael D’Antonio

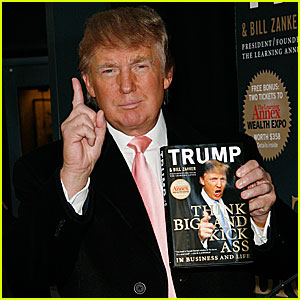

The projection of Trump as a successful Atlantic City casino operator is also being revealed as so much smoke and mirrors. He built Trump Taj Mahal on a shaky  foundation of high-interest junk bonds, which soon had him deeply in hock to his creditors. Detractors also point out that Trump’s successful is mainly as a promoter — of Donald Trump. “Purely on his track record as a real estate developer and casino operator, Trump hasn’t demonstrated that he’s a particularly good dealmaker,” says TrumpNation author Timothy L. O’Brien, who adds, “He never really buckled down and learned the nuts and bolts of running a casino.”

foundation of high-interest junk bonds, which soon had him deeply in hock to his creditors. Detractors also point out that Trump’s successful is mainly as a promoter — of Donald Trump. “Purely on his track record as a real estate developer and casino operator, Trump hasn’t demonstrated that he’s a particularly good dealmaker,” says TrumpNation author Timothy L. O’Brien, who adds, “He never really buckled down and learned the nuts and bolts of running a casino.”

“A lot of people got stuck holding the bag, and he didn’t. So people resented him for that and felt serious financial pain,” adds Temple University historian Bryant Simon. The pain was serious indeed: redemption of debt at less than a penny on the dollar if you were an unsecured creditor. “It was a joke among all the subs that you’d tack on an extra 10% onto your bids. He was slow pay, everybody knew,” says United States Roofing Corp. President Dave Farragut. At least Trump enjoyed good relations with labor union Unite-Here Local 54. Says former Trump Plaza cocktail waitress Theresa Volpe, “He was very receptive to our union and our benefits and pension plan.”

Still, former Atlantic City mayor and current state Sen. James Whelan (D) says, “I think his personality that people are experiencing on the campaign trail. is something that we experienced here … I experienced it firsthand. He can be obnoxious.” He downplays Trump’s role as a Boardwalk casino magnate, noting that all three Trump casinos were begun by other companies, including Harrah’s Entertainment and Resorts Atlantic City.

Still, former Atlantic City mayor and current state Sen. James Whelan (D) says, “I think his personality that people are experiencing on the campaign trail. is something that we experienced here … I experienced it firsthand. He can be obnoxious.” He downplays Trump’s role as a Boardwalk casino magnate, noting that all three Trump casinos were begun by other companies, including Harrah’s Entertainment and Resorts Atlantic City.

Anyway, it’s a good thing the casino industry is at least temporarily rid of Trump, considering the putrid excuse for a human being that he is.

Just the news sir, don’t have a personal vendetta against any political candidate. We already have Jon Ralston in Las Vegas.